Deep Dive: Cellulitis Antibiotics Review

/Introduction

It’s finally summer, when people get outside, get dirty, and invariably develop skin reactions that make us question whether that “lumpy, bumpy” patch is contact dermatitis or actually brewing badness. Skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) is a frequently presenting symptom to the emergency department (ED), with cellulitis accounting for an estimated 2.3 million ED visits annually.[1] This post will review the diagnostic approach to cellulitis and factors that influence antibiotic therapy.

Cellulitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissue that can be differentiated from similar non-infectious and infectious presentations like erysipelas, which is more superficial and has distinct borders, and purulent cellulitis, which occurs around an abscess. Streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common causative organisms with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) implicated in an increasing proportion of SSTIs presentations. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus spp. have also been identified in complicated SSTI cases.[2,3]

Diagnosis

Cellulitis is a clinical diagnosis. While the familiar rhyme of “rubor, dolor, calor, and tumor” (referencing the erythema, pain, warmth, and swelling that often accompanies cellulitis) is easy to remember, these descriptors are fairly non-specific.

One of the first distinctions that providers need to make is between purulent and non-purulent cellulitis – essentially, is this an abscess that needs incision and drainage? Physical examination has demonstrated poor inter-rater agreement and accuracy for distinguishing simple cellulitis from skin abscess.[4] To assist us with diagnostic accuracy, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been an emerging adjunct in the emergency department. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated a pooled sensitivity of 96.2% and specificity of 82.9% for POCUS in determining whether a soft tissue infection was due to an abscess versus cellulitis.[5]

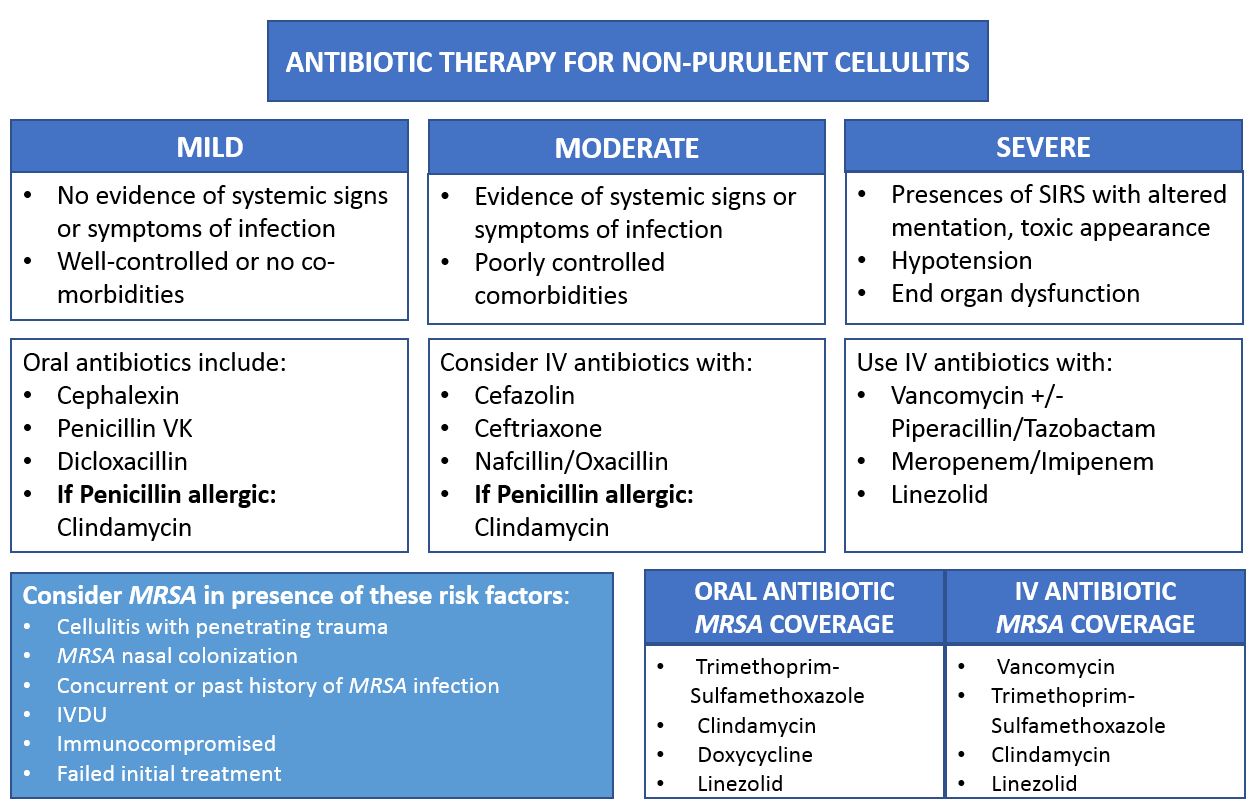

The next decision that influences antibiotic choice, as well as the decision to admit a patient, relates to severity of infection. Infection with cellulitis is characterized as mild, moderate, or severe based on signs and symptoms of systemic infection and the presence of co-morbidities. Patients with mild cellulitis have no signs of systemic infection, are afebrile, and may have well-controlled co-morbidities. Patients with moderate infection have systemic signs of infection and/or have poorly controlled co-morbid conditions whereas those with severe infection meet “moderate” criteria and additionally present with altered mental status or signs of septic shock.[6]

Antibiotic Choice

In the era of MRSA, the treatment of cellulitis has evolved to encompass an array of practice patterns with varying evidence bases. The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) updated their guidelines in 2014 to cover the diverse spectrum of SSTIs, including the complicated and antibiotic resistant etiologies.

For the treatment of mild infection, oral therapy and antimicrobial agents effective against streptococci and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) should be sufficient. Cephalexin is a common choice, and Penicillin VK and Dicloxacillin are also options. If a patient has a true penicillin allergy, then Clindamycin is an acceptable alternative. For patients with moderate and severe cellulitis, systemic antibiotics are indicated. The IDSA recommends 5 days of treatment for mild cellulitis, though therapy should be extended if the infection has not improved in that time frame. Also, local antibiograms should be taken into consideration when considering initial coverage.

Historically, some providers have opted to use two antibiotics for mild cellulitis with the presumptive thought of covering occult MRSA cellulitis and thus decreasing rates antibiotic failure. The IDSA does not currently support this practice, and a study by Moran et. al in 2017 provides further support for this recommendation. Comparing cure rates in a Cephalexin plus placebo versus a Cephalexin plus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) group, they found that the addition of TMP-SMX did not result in an increased clinical cure rate in the per protocol analysis. Interestingly, the modified intention-to-treat analysis did demonstrate a clinically important difference that favored the Cephalexin and TMP-SMX regimen. However, this may reflect poor protocol adherence in the Cephalexin only group and warrants further investigation rather than a deviation from current IDSA guidelines.[7,8]

There are exceptions to every rule, and the IDSA does recommend covering for MRSA in patients whose cellulitis is associated with penetrating trauma, who have evidence of nasal colonization or MRSA infection elsewhere, or who have a history of injection drug use as well as in most patients who are severely compromised or who have evidence of severe cellulitis. TMP-SMX, Clindamycin, Doxycycline, or Linezolid are oral antibiotics that provide effective MRSA coverage for patients with mild cellulitis.[6]

Interestingly, a 2019 retrospective review by Yadav et al. analyzed over 500 patient charts to ascertain predictors of treatment failure for cellulitis treated with oral antibiotics (defined as hospitalization, change in the class of oral antibiotics, or transition to IV therapy after 48 hours of oral therapy). They identified tachypnea at triage, history of chronic ulcers, history of MRSA colonization or infection, and cellulitis in the past 12 months as significant predictors of treatment failure and concluded that these risk factors should be considered when weighing whether to initiate intravenous versus oral antibiotics. However, consideration of these risk factors when determining need for MRSA coverage may warrant further study as well.

Intravenous Versus Oral Therapy

Several randomized clinical trials have compared intravenous to oral antibiotics in the treatment of erysipelas and cellulitis and found that oral therapy variably had a higher cure rate and lower rate of recurrence in clinically similar patients. A 2010 Cochrane meta-analysis concluded that oral therapy was superior to IV therapy (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73-0.98). Of course, there are some patients for whom IV therapy is more appropriate whether MRSA is suspected or not. IV therapy should be considered when patients can’t tolerate PO, if they require a particularly high dose or need to achieve rapid peak antibiotic levels, or if they have impaired absorption. [9,10] In patients with severe cellulitis, the IDSA recommends empiric coverage with Vancomycin plus Piperacillin-Tazobactam or Imipenem/Meropenem.

Take Home Points

The initial steps in determining appropriate antibiotic therapy for cellulitis include confirming the diagnosis of non-purulent cellulitis and characterizing cellulitis severity.

Ultrasound is a reliable, sensitive tool to distinguish purulent and non-purulent cellulitis.

A single oral antibiotic effective against streptococci and MSSA such as Cephalexin is sufficient for uncomplicated, mild cellulitis with no other complicating risk factors.

The IDSA does not recommend covering for MRSA in patients with no known risk factors and who do not have severe cellulitis. Accepted risk factors for MRSA include cellulitis associated with penetrating trauma, MRSA nasal colonization, concurrent or past history of MRSA infection, IV drug use, immune-compromised conditions, and failed initial treatments, though recent studies suggest there are other conditions that may warrant further study.

AUTHOR: Colleen Laurence, MD, MPH

Dr. Laurence is a PGY-2 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

Post and peer editing: SHAN MODI, MD

Dr. Modi is a PGY-3 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and curator of the ‘Minor Care Series’

FACULTY EDITOR: EDMOND HOOKER, MD

Dr. Hooker is an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and Faculty Editor of the ‘Minor Care Series’

Resources

Khachatryan A, Patel D, Stephens J, Johnson K, Patel A, Talan D. Skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs) in the emergency department (ED): Who gets admitted? http://content.stockpr.com/duratatherapeutics/db/Publications/2774/file/5-6e_SAEM_Poster.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2016.

Esposito S, Noviello S, Leone S. Epidemiology and microbiology of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(2):109–115. Accessed on May 17, 2019.

Eron LJ, et al. Managing skin and soft tissue infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(suppl 1):i3–i17.

Butler KH. Incision and drainage. In: Roberts J, Hedges J, eds. Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2004. pp 717–26

Barbic D, Chenkin J, ho DD, Jelic T, and Scheuemeyer FX. In patients presenting to the emergency department with skin and soft tissue infections what is the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of abscess compared to the current standard of care? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017; 7 (1): e013688.

Stevens DL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, et al. Effect of Cephalexin Plus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole vs Cephalexin Alone on Clinical Cure of Uncomplicated Cellulitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017; 317 (20): 2088-2096.

Swaminathan A. Initial Antibiotic Choice in Uncomplicated Cellulitis. R.E.B.E.L. EM. https://rebelem.com/initial-antibiotic-choice-in-uncomplicated-cellulitis/ . Accessed on May 17, 2019.

Justin Morgenstern, "Magical thinking in modern medicine: IV antibiotics for cellulitis", First10EM blog, April 2, 2018. Available at: https://first10em.com/cellulitis-antibiotics/. Accessed on May 18, 2019.

Kilburn SA, Featherstone P, Higgins B, Brindle R. Interventions for cellulitis and erysipelas. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010; PMID: 20556757